Children who were educated in the small rural country schools in the West Milford until the mid-1940s, when the last of these schools closed, learned early in their lives about the benefits of self-education.

Early school boards struggled to find enough money to buy basic-skills books for the students.

There was little money for extra library books, with town and school budgets required to be affordable for a hard-working population of people who were not paid much money at the Pequannock Rubber Co. mill and other area factories. Some people had businesses, and a few others were farming.

The town’s earliest library, started by volunteers, was in a storefront in the Davenport complex of small stores on Union Valley Road at the Macopin Road intersection.

Initially, books were gathered through donations. This library was used mostly by West Milford Village residents. Those living in other parts of the township shopped in Butler, Bloomingdale, Pompton Lakes or Warwick, N.Y., stores closer to their homes.

Their main and sometimes only reason to go to the current town center area was to vote on primary and general election days or to pay their quarterly tax bills at the town hall.

New Jersey had a school library book-lending program in the 1940s. A few times each year, a driver with a small truck carried books loaned by the state to be delivered to each school.

He took books that students had been reading for the past few months to another school, where they would remain until another book exchange. It was a kind of book-rotation program that I, as one of the students who had use of the books, remain grateful for.

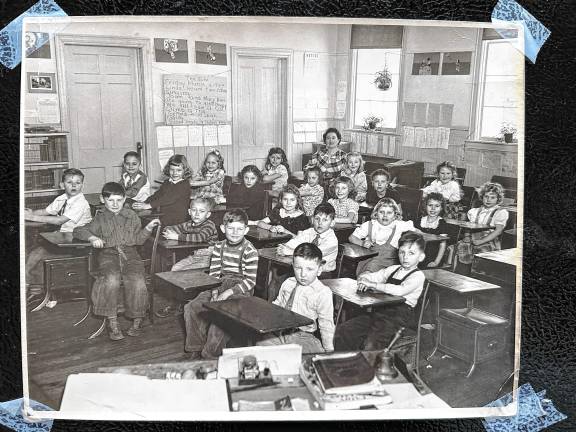

We had time to explore and learn independently while the teacher was working with students in the different grade levels in a room housing first-, second- and third-graders. The classes for students in higher grades were held in an adjoining room.

Parent Teacher Associations (PTAs) were organized and active in the in the rural schools of West Milford by the 1940s. Often, these parents and their friends earned funds to purchase projectors (16-millimeter) and other extra things that school boards did not have taxpayer money to buy.

As a student for four years in the primary grade classrooms at Echo Lake School, I recall my mother, Verina Mathews Genader, chose films from an available list that were loaned to schools for free from the state library at Trenton.

Sometimes the films she ordered were also of interest to adults so she showed them as part of a PTA evening meeting at the school.

The films came and were returned by U.S. mail delivery. Walter Snel, the mobile mailman for the Apshawa/Echo Lake section, delivered them.

He and Verina knew each other from Butler High School, as members of the Class of 192I. In that day, area towns did not have high schools and they sent their students to BHS.

I remember that the children were fascinated by one of the first films to arrive. It featured the life cycle of salmon and their swim up river back to the place where they were born to lay their eggs and create a new generation.

Before the familiar Dick, Jane and Sally, the Scott Foresman learn-to-read series was used in the West Milford rural schoolhouses. The Winston readers were used for reading instruction.

The series featured stories about the lives of siblings named Mary Ann and Junior. The brother and sister had story lines with activities and events typical of children in that day. The reading text did not have a vocabulary much different than the Dick, Jane and Sally books.

Student learning opportunities in the rural schools were endless, with the teacher having the freedom to give students time and independence to explore and learn about subjects they were interested in.

Many of the children helped teachers with younger classmates who needed extra help in various subjects.

One of the benefits of the two-room schoolhouse days was that the teacher created the curriculum and could change the plan when a high-interest episode happened. There was no daily plan as is the procedure today.

Learning situations were directed at the individual interests and needs of the students. If a child found something outdoors during recess or brought something interesting from home, the teacher could seize the moment and change her original lesson plan to the new topic.

Creative writing in Verina’s classroom usually followed language arts lessons with the child working at their level of development. Other subjects related to the main topic more often than not made it a multisubject adventure. – a most valuable learning experience.

Classroom dog

Some years after my eighth-grade graduation from Echo Lake School, Butler High School, then Jersey City State College, I was a first-grade teacher at Lenox School in Pompton Lakes.

My mother told me of an event in her classroom that brought attention from the Newark News, a daily newspaper distributed throughout the northern part of the state.

The subject was a spontaneous learning opportunity that probably happened in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Verina was teaching in the primary grade room of Echo Lake School on a Friday afternoon in the middle of January when something unusual happened. I have her notes from that day.

She wrote that the third-grade class was studying Eskimo life “including occupations, climate and habits of neighbors of the far north.” She told of an unexpected learning experience for the students that provided interesting lessons in science, math, creative writing and reading for days to follow. Student achievement in this type of lesson was usually remarkable because the topic was something that the children were curious about.

“The entrance door of the little two-room Echo Lake School was partly open in order to let some fresh air circulate,” Verina wrote. “As the children were completing their assignments, they were startled by the appearance of a little white Spitz dog. The animal apparently came up the outdoor steps and walked into the classroom.

“The children were overjoyed and they welcomed the little dog gleefully. The gentle animal stopped at the desk of each child. After receiving a gentle pat or a shake of her paw, she rewarded her new friends with a warm, loving lick. The new visitor then found a comfortable place on the cozy hearth in front of the huge warm furnace and settled in.”

There were no telephones, cellphones or computers at the rural schoolhouses or homes. The nearest phone or type of communication with anyone outside the school was at the Gulf gas station and general store owned by Dave Mathews, Verina’s brother.

It was a considerable distance away, at the corner of Germantown and Macopin roads. In an emergency, an eighth-grade boy would be sent there to phone Police Chief John Moeller for help.

Without a dispatcher in the Police Department office in the balcony of what is now the West Milford Museum, all calls from area towns went to the police radio station in Pompton Lakes, and whoever was on desk duty there radioed West Milford police.

It was too close to the end of the school day to send anyone to the store for guidance about the school-visiting dog.

“As time neared for dismissal, the students spoke in unison, asking if the white Spitz visitor could be kept as a school dog,” Verina wrote in her notes. “I told them I would speak to Police Chief Moeller and see what needed to be done.

“Later when I called him on the telephone from home, John said all they needed to do to keep the dog was to get a license for it. The children happily contributed to pay the fee, which was $1.25 for the year. That created some unplanned math and other lesson subjects.”

Helen Manetas, the school district nurse, volunteered to purchase the dog license at West Milford Town Hall. She agreed with the teacher that having a school dog would provide some valuable learning experiences.

Somewhere along the way, Moeller spoke with Celia King, a leading reporter for the Newark News newspaper. (John probably told Celia about the dog in the schoolhouse when she was doing her daily phone check with him for any news story material from the Police Department.)

The children named the dog Mitzie, and she routinely walked to school with the teacher after sleeping by the warm furnace in the basement of her home at night.

Mother and puppies

Before long, it became apparent to Verina that Mitzie was pregnant and would be having puppies. On hearing this news, the children were curious and took especially good care of their dog on her daily visits to the classroom.

When birth time was getting near, Mitzie no longer went to school and instead stayed at her warm comforting place at the teacher’s home. One evening, Mitzie’s puppies were born.

Verina continued to care for the dog and babies at home for a while. When the puppies were old enough, they went with Mitzie to the school and there were more natural lessons about animal habits and care.

The school nurse was on hand to answer any questions they had about the mother dog and her puppies. Eventually the puppies had permanent homes with some of the children and their parents. Mitzie also had a permanent home with one of the families.

It was an exciting day when the reporter arrived at Echo Lake School with a photographer. The children were thrilled when her story and their photos with Mitzie were published in the newspaper.

This was a successful learning experience, and there’s no doubt that the children in school at the time will always remember Mitzie, the classroom dog.

Health and safety laws today would not allow such informal lessons without controls.

Both the police chief and school nurse saw no problems with the dog going into the classroom without a full exam by a veterinarian. People did not think of health and safety regulations. To them, everything was based on common sense.

When emergencies happened, they handled situations in what they felt was an appropriate way. It was a different and very happy era, and those of us who were part of it would not trade the exciting learning experiences and adventures we had in the rural schools, where we spent happy days, learned so much and made lifelong friends.