Before the invention of refrigeration, ice from North Jersey lakes initially was the main source for keeping food fresh. Later, it gradually enabled new products, including chilled drinks, ice cream and medicines to be marketed.

Winters were much colder and longer here in the 1800s and early 1900s than they have been in recent years. The lakes froze solid and people walked, skated, and took animals and equipment onto it.

Ice harvesting became a major business. Large ice companies were located at Greenwood Lake, Echo Lake, Oak Ridge, Stockholm, Lake Hopatcong and countless other places.

The late Ernest Sanders was superintendent of the ice business at Greenwood Lake. It was operated by the Mountain Ice Co. of Hoboken from 1919 until 1928, when the company shut this business location.

The owners of this company also had an ice business at Gouldsboro, Pa., and other locations at the time.

Sanders said two ice houses operated as one unit at Greenwood Lake. One was in West Milford and the other was in Warwick, N.Y. During the winter, 200 men were employed at Greenwood Lake with from 20 to 40 horses also working on the ice-covered lake..

Not all workers were from the local population. Some came by train, and there were sleeping and dining accommodations for as many as 100 men, a chef and others working in this phase of the business.

The year-round workday was 10 hours with average pay from 30 to 32 cents an hour. The highest salary of 55 cents an hour was paid to a “carman” in the summer. This employee’s job was to inspect the railroad cars and ensure they were in safe working condition.

Sanders recalled that workers were not too tired at the end of their day to go fishing or dancing.

He did not begin working at the Greenwood Lake ice harvesting location until the end of World War I. However, the ice harvesting business at the lake had started years earlier.

Dave Pieters, a former West Milford resident, said his grandfather John Milton Rhinesmith used to sharpen the blades of the ice-cutting machines. These were pulled by a team of horses with cleats on their shoes.

Pieters remembered when the horses got on some thin ice and fell through it into the water. He also remembered that the ice was shipped by rail train to Jersey City with stops along the way. The trip usually started with 17 cars; often only three were remaining at the final stop.

Pieters spoke of “a place referred to as dead man’s curve where a train going down from Greenwood Lake left the tracks and many people were hurt and some were killed.”

His grandfather went to his winter job at the lake from home every morning “with his horse and buggy, lantern and a heavy robe over himself to try to keep warm.”

The Greenwood Lake Ice Co., as it was first known, was established by Edward Cooper (1824-1905) and Abram Hewitt (1822-1903). Cooper, son of Peter Cooper, was mayor of New York City from 1879 to 1880 and Hewitt was mayor from 1887 to 1888.

Edward Cooper and Hewitt traveled by ship to Europe together, and on the return trip, they were shipwrecked. From that time on, Hewitt was regarded as a member of the Cooper family.

He married Cooper’s only daughter, Sarah Amelia. The couple had six children. Peter Cooper financially backed his son and Hewitt when they started the Trenton Iron Works business.

If there was no snow on the ice, workers and the teams of horses began cutting it at daybreak. If there was snow, it had to be cleared before cutting could start.

If the ice was 10 inches thick, it was considered deep enough to be a safe working day. Sometimes there would be just one man leading a horse with another leading the plow. There were some men with teams of horses that pulled knife-sharp cutting blades.

In the 20th century, these were replaced by motorized circular saws. In cutting the ice, parallel lines were carved into the surface first. Then the men worked at right angles to those lines. They ended up with a checkerboard ready to be cut into manageable ice cakes.

The tools were long-bladed saws, much like those used by a lumberjack to complete the job.

The icehouses were large structures. Those at Greenwood Lake and Lake Hopatcong, the largest lakes, were the largest ice producers.

When the frozen cakes were moved into the icehouses, they were stacked in orderly rows. Each tier was covered with hay or sawdust to act as insulation when warm weather returned.

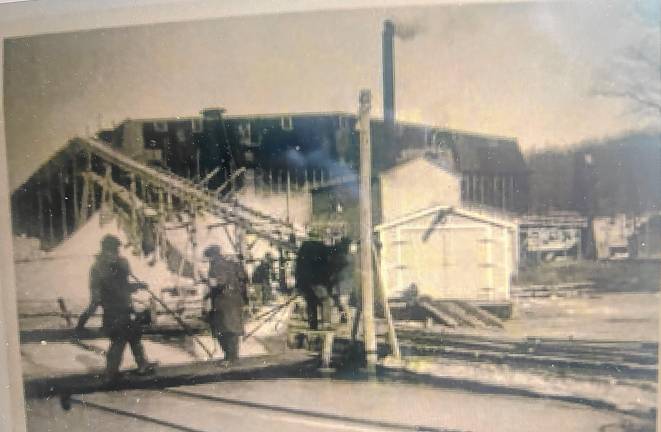

After being cut, the ice cakes were floated to the icehouse through channels of water. At Greenwood Lake there was a wooden bridge over the channel where a half-dozen men and boys with long iron picks cut the ice cakes into floats that were marked out and already cut through. The ice cakes were then pushed into a conveyer that carried them up into the icehouse to be slid into place for cross stacking.

The cakes of ice were cut about 16 inches by 24 inches.

Operations at Greenwood Lake went well when the weather was calm and clear with the ice cakes breaking even. That could change quickly if there was wind spraying water into the cuts.

If that sudden freezing happened, the ice cake, breaking uneven, had to be pushed aside and discarded. One of the problems at the Greenwood Lake ice business was where to store waste ice.

It was not uncommon for a day to turn warm, creating a soft spot in the ice that resulted in both a horse and a man splashing into the frigid water. There were the times when a conveyer jammed or broke and everyone in the area was soaked as the cakes of ice splashed down into the lake. The harvest on the New York end of the lake was 44,000 tons, and on the New Jersey end, it was 33,000 tons annually.

As large pieces of ice were pulled up into the ice house by the conveyer, small pieces were piled up until they melted, sometimes as late as mid-June.

The ice storage building was about 300 feet by 250 feet wide. It had six compartments, each about 50 feet wide. The structure on the New Jersey side of the lake was from 35 to 40 feet tall. The building on the New York side was larger and made of tile.

Ice workers at Greenwood Lake included people from the Ryerson and Richards families. There were also workers from Pine Island, N.Y. There was 10 percent shrinkage in the icehouse.

The ice was loaded on a train at Greenwood Lake between 5 and 7 p.m. and delivered to the cities the same night. The train was a special that only transported ice. The load was weighed in Midvale, then headed for Jersey City, dropping ice at various locations.

The railroad station at Greenwood Lake was at the end of the Erie line and there was a large turntable to turn the trains around and head them toward Jersey City.

Bill Sando, a former Awosting resident, recalled that people walked across the frozen lake to board the passenger train heading south, and they had to be careful not to fall through the ice at the wide once-frozen fields where ice was cut for the refrigeration business.

Sando and his grandfather William Fox saw some men ice-boating on the lake when the boat slipped through a hole in the ice and fell into the water. He remembered his grandfather helping get the men to safety.

Technical advances in refrigeration systems ended the need for the ice-harvesting business. This created a severe loss of revenue for the rail transportation business too.

Some businesses moved to New England, where winters were longer.