A year before Jack Ryan was hired as West Milford’s second full-time police officer in 1942, lone lawman John Moeller may have been critically shot if a young gunman handled his gun differently.

This story of a 1941 shootout at the Germantown Road summer home of the Otto Hill family of Secaucus begins on a biting cold, clear early February morning.

My mother, Verina Mathews Genader, and I were walking along Germantown Road from our Macopin Road home to the two-room Echo Lake Schoolhouse, where she would spend the day teaching the primary grades. I was a student there.

As we approached the Fountain Road intersection, my mother noticed that a front window in Hill’s vacation home (where the St. Joseph Convent building is located) was halfway open, something that was not the case the previous day.

She knew that the owner and his family were not returning there until May.

With the school day to start soon and no telephones in the immediate area, she could only continue the daily routine without being able to alert anyone about the open window.

Josephine Marion, the teacher in the upper-grade room, drove her car to the school each day, parked it in the driveway outside the school and never bothered to lock it.

It was the same on that beautiful winter routine school day. After a morning of reading, writing and arithmetic, the students were looking forward to morning and afternoon recess, when everyone usually played softball in the school yard with the teacher pitching for both teams. The Hill family house was next door.

Little did the teachers know that on that day, two young boys from Paterson who had left their homes two days earlier seeking an adventure, had broken into the Hill family house and were settled in with an arsenal of guns.

The finale would be a shootout with local lawmen, and the boys would be convicted of juvenile delinquency charges that brought them three years of confinement in the New Jersey State Reform School at Jamesburg.

After the routine end of each school day, a school bus, owned and operated by Harold Rhinesmith of Otterhole Road, transported Apshawa and Weaver Road students home.

A station wagon owned and operated by Henry Vreeland of Macopin took Germantown Road, Wellertown and Macopin Road students to their homes.

At the end of that February school day, the teachers as usual put their classrooms in order, locked the school doors and went home. Mrs. Marion’s car with the keys in it was there as usual for her when she was ready to leave.

Father aids officer

My father, Arthur Genader, like many men in the Macopin/Apshawa/Echo Lake areas of the township in the 1930s and ’40s, worked in the Pequannock Rubber Co. Mill in Butler.

He arrived home from completing his day shift about the same time that my mother returned from her day at the school.

Like many men throughout the township, he was one of those called to duty with Moeller when a “special police” officer’s help was needed.

Verina immediately told him about the open window at the Hill house and a phone call report went to Moeller. Ryan was a member of the “special police” force before being appointed as the second full-time officer the next year.

Moeller and his two officers (Ryan and Genader) went to the Hill house to investigate. Moeller saw that a rug covered a broken window in a rear door in the back of the house. Trying to reach in to unlock the latch, he broke more glass in the window.

As the splintered glass particles fell to the floor, six gunshots were fired over his head. With his two officers, Moeller retreated.

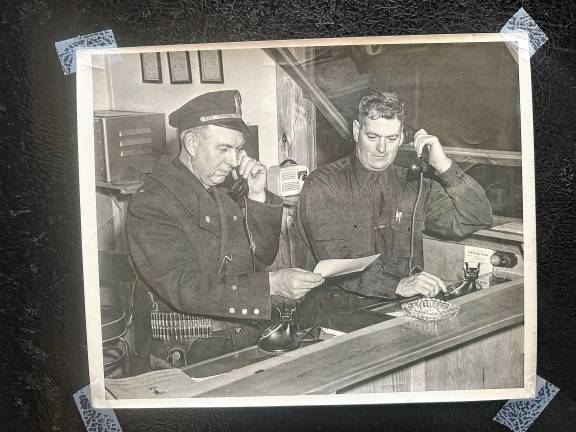

The police radio dispatcher at Pompton Lakes called in backup help from area police departments, as requested by Moeller.

The police were unaware that the fugitives with whom they were exchanging gunfire were two boys ages 14 and 12. Moeller’s demand that whoever was in the house come out with hands in the air was met with more gunfire.

The shooting between police and those in the house continued for three and a half hours. State police from the Morristown station were dispatched to the scene with tear gas to end the long, dangerous episode.

The first tear-gas bomb that they put into the building through a rear window did not bring anyone out of the house - but a second one did.

Police were shocked to see two disheveled boys reluctantly come out the front door, tears streaming from their eyes. It was 1:05 a.m.

The boys, barricaded in the house, had eight stolen guns and had fired more than 100 shots at police.

Making an example

It was a different time. Unlike today, when names of juveniles are not released, Moeller told reporters that he wanted names of the two boys published in newspaper reports - and they were. He felt that they had committed crimes and the public should know.

The newspapers complied by printing not only the names, but they also sent photographers to take photos of the boys to appear with the article.

The boys lived in Paterson, one with his mother and stepfather, and the other with his parents. One was a lanky sixth-grader who was said to be a bit behind in his schoolwork. The other was a short seventh-grader. Neither boy had a previous record of being in trouble.

At first, the two adventurers broke into a Paterson garage with an 8-year-old boy tagging along. They were spotted by a street patrol officer who fired a gun in the air and apprehended the younger child.

The two older boys ran through Paterson’s back streets and came upon an open parked car with the keys in the ignition.

Neither boy had driven a car before, but one had watched his mother drive when he was her passenger. He remembered what she did to operate the vehicle and found he was able to do so too.

In the next 48 hours, they were involved in stealing two more cars. Traveling up Mariontown Hill on Macopin Road coming from Bloomingdale into West Milford, the final car ran out of gas.

They ditched it and proceeded on foot until they came to Mountain Spring Lake, where they found unoccupied summer vacation cabins, broke in and raided them.

Taking loot that included guns with them, they slept one night in a sandpit and the next night in an outdoor dog kennel. The next day, they found the Hill house. They broke inand found a good supply of canned food and most anything else they needed to hole up for a long time.

Police said the boys never were able to answer why they embarked on the escapade, nor could they give any reason for their actions.

It was a frightening time for me, as a 9-year-old, aware that there was a shootout - and that my father could be killed.

Western movie shootouts that we saw in films shown at the Butler movie house on Arch Street were very familiar.

I remember my mother holding my brother, Bill, and me with her arms tightly around us. We were by an open window as we listened to the crack of the gunshots at the nearby Hill house.

How frightened she must have been!

Before the year was over, this traumatic experience was overshadowed by something more powerful and frightening. On Dec. 7, 1941, we heard a radio report by President Franklin Roosevelt that Japanese war planes had attacked the American military installations in the Pacific, with the most devastating strikes at Pearl Harbor, the Hawaiian base where much of the U.S. Navy fleet was moored.

I remember Roosevelt’s description of it being “a day that will live in infamy.”

As my late contemporary friend John Fredericks would say many times in passing years: “Nothing remains the same.” His words remain true.